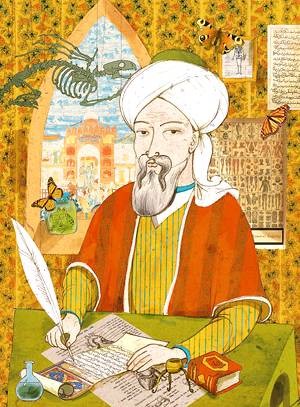

Avicenna, Arabic Ibn Sīnā, in full Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā, (born 980, near Bukhara, Iran [now in Uzbekistan]—died 1037, Hamadan, Iran), Muslim physician, the most famous and influential of the philosopher-scientists of the medieval Islamic world. He was particularly noted for his contributions in the fields of Aristotelian philosophy and medicine. He composed the Kitāb al-shifāʾ (Book of the Cure), a vast philosophical and scientific encyclopaedia, and Al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb (The Canon of Medicine), which is among the most famous books in the history of medicine.

Life and education

This great scientist was born in around 980 A.D in the village of Afshana, near Bukhara, now in Uzbekistan, which is also his mother’s hometown. His father, Abdullah an advocate of the Ismaili sect, was from Balkh which is now a part of Afghanistan.

Ibn Sina received his early education in his home town and by the age of ten he became a Quran Hafiz (he had memorized the Quran). He had exceptional intellectual skills which enabled him to overtake his teachers at the age of fourteen. At about 13 years of age he studied medicine with a number of teachers. At the age of 16, he established himself as a respected physician. Besides studying medicine, he also dedicated much of his time to the study of physics, natural sciences and metaphysics.

Avicenna began his prodigious writing career at age 21. Some 240 extant titles bear his name. They cross numerous fields, including mathematics, geometry, astronomy, physics, metaphysics, philology, music, and poetry. Often caught up in the tempestuous political and religious strife of the era, Avicenna’s scholarship was unquestionably hampered by a need to remain on the move.

His knowledge of medicine brought to the attention of Nuh ibn Mansur, the Sultan of Bukhara of the Samanid Court, whom he treated successfully. In 997, Avicenna was hired as a physician by Nun ibn Mansur, and he was permitted to use the sultan’s library and its rare manuscripts allowing him to continue his research. This training and the library of the physicians at the Samanid court assisted him in his philosophical self-education. The sultan’s royal library was considered one of the best kinds in the medieval world at the time.

While in the company of ʿAlā al-Dawla, Avicenna fell ill with colic. He treated himself by employing the heroic measure of eight self-administered celery-seed enemas in one day. However, the preparation was either inadvertently or intentionally altered by an attendant to include five measures of active ingredient instead of the prescribed two. That caused ulceration of the intestines. Following up with mithridate (a mild opium remedy) a slave attempted to poison Avicenna by surreptitiously adding a surfeit of opium. Weakened but indefatigable, he accompanied ʿAlā al-Dawla on his march to Hamadan. On the way he took a severe turn for the worse, lingered for a while, and died in the holy month of Ramadan.

Influence in medicine

Despite a general assessment favouring al-Rāzī’s medical contributions, many physicians historically preferred Avicenna for his organization and clarity. Indeed, his influence over Europe’s great medical schools extended well into the early modern period. There The Canon of Medicine (Al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb) became the preeminent source, rather than al-Rāzī’s Kitāb al-ḥāwī (Comprehensive Book).

Avicenna’s penchant for categorizing becomes immediately evident in the Canon, which is divided into five books. The first book contains four treatises, the first of which examines the four elements (earth, air, fire, and water) in light of Greek physician Galen of Pergamum’s four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile). The first treatise also includes anatomy. The second treatise examines etiology (cause) and symptoms, while the third covers hygiene, health and sickness, and death’s inevitability. The fourth treatise is a therapeutic nosology (classification of disease) and a general overview of regimens and dietary treatments. Book II of the Canon is a “Materia Medica,” Book III covers “Head-to-Toe Diseases,” Book IV examines “Diseases That Are Not Specific to Certain Organs” (fevers and other systemic and humoral pathologies), and Book V presents “Compound Drugs” (e.g., theriacs, mithridates, electuaries, and cathartics). Books II and V each offer important compendia of about 760 simple and compound drugs that elaborate upon Galen’s humoral pathology.

Unfortunately, Avicenna’s original clinical records, intended as an appendix to the Canon, were lost, and only an Arabic text has survived in a Roman publication of 1593. Yet, he obviously practiced Greek physician Hippocrates’ treatment of spinal deformities with reduction techniques, an approach that had been refined by Greek physician and surgeon Paul of Aegina. Reduction involved the use of pressure and traction to straighten or otherwise correct bone and joint deformities such as curvature of the spine. The techniques were not used again until French surgeon Jean-François Calot reintroduced the practice in 1896. Avicenna’s suggestion of wine as a wound dressing was commonly employed in medieval Europe. He also described a condition known as “Persian fire” (anthrax), correctly correlated the sweet taste of urine to diabetes, and described the guinea worm.

Avicenna’s influence extends into modern medical practice. Evidence-based medicine, for example, is often presented as a wholly contemporary phenomenon driven by the double-blind clinical trial. But, as medical historian Michael McVaugh pointed out, medieval physicians went to great pains to build their practices upon reliable evidence. Here, Avicenna played a leading role as a prominent figure within the Greco-Arabic literature that influenced such 13th-century physicians as Arnold of Villanova (c. 1235–1313), Bernard de Gordon (fl. 1270–1330), and Nicholas of Poland (c. 1235–1316). It was Avicenna’s concept of a proprietas (a consistently effective remedy founded directly upon experience) that permitted the testing and confirmation of remedies within a context of rational causation. Avicenna, and to a lesser extent Rhazes, gave many prominent medieval healers a framework of medicine as an empirical science integral to what McVaugh called “a rational schema of nature.” This should not be assumed to have led medieval physicians to construct a modern nosology or to develop modern research protocols. However, it is equally ahistorical to dismiss the contributions of Avicenna, and the Greco-Arabic literature of which he was such a prominent part, to the construction of modalities of care that were fundamentally evidence-based.

Legacy

It is difficult to fully assess Avicenna’s personal life. Most of what is known of Avicenna is found in the autobiography dictated to his longtime protégé al-Jūzjānī. Avicenna’s mercurial wit and expansive brilliance won him many friends, but his flouting of Islamic puritanical conventions earned him even more enemies. Avicenna also appears to have been a lonely, brooding figure, whose efforts at self-promotion were often tempered by a cagey instinct for survival in a politically volatile world. Despite Avicenna’s personal strengths and weaknesses, his intelligence was great in theoretical and practical matters.

In addition to Avicenna’s philosophy having been readily incorporated into medieval European Scholastic thought, his synthesis of Neoplatonic and Aristotelian thought and his encompassing of all human knowledge of the time into well-organized accessible texts make him one of the greatest intellects since Aristotle. British philosopher Antony Flew’s appraisal of Avicenna as “one of the greatest thinkers ever to write in Arabic” expresses the modern scholarly assessment of the man.

In medicine, Avicenna exerted a profound influence over the schools of Europe into the 17th century. The Canon was subjected to increasing criticism by Renaissance instructors, yet, because Avicenna’s text adhered to the practice and theories of medicine described in Greco-Roman texts, instructors used it to introduce their students to the basic principles of science. Avicenna, never wanting for enemies, was as true in death as in life. Medieval physician Arnold of Villanova berated Avicenna as “a professional scribbler who had stupefied European physicians by his misinterpretation of Galen.” But such an assertion is heavy-handed. Indeed, without Avicenna much knowledge would have been lost. Furthermore, his resilience over the centuries belies Villanova’s conclusion. Lecturing in 1913, Canadian physician and professor of medicine Sir William Osler described Avicenna as “the author of the most famous medical text-book ever written.” Osler added that Avicenna, as a practitioner, was “the prototype of the successful physician who was at the same time statesman, teacher, philosopher and literary man.”

Avicenna’s continued importance as a towering figure in Islamic history may be seen in his tomb at Hamadan. Even though it had fallen into disrepair by the early 20th century, Osler noted that “the great Persian has still a large practice, as his tomb is much visited by pilgrims, among whom cures are said to be not uncommon.” In the 1950s the tomb was refurbished and transformed into an impressive mausoleum adorned with an imposing Mughal-inspired tower, and a museum and 8,000-volume library were added as well. Avicenna’s resting place remains a major stop for tourists in the region. Now, as when he was alive, the great physician and philosopher continues to attract the attention of scholars and the public alike.

Timeline

17 years of efforts towards the development of healthcare in the nation.